The increasing feasibility of automation has created questions about the future of work and its potential for displacing workers.

Jobs and Automation: How will the Future Work?

“When technology advances too quickly for education to keep up, inequality generally rises.”

Erik Brynjolfsson

Director of the MIT Initiative on the Digital Economy

The rapid pace of technical advances and the increasing feasibility of automation has created questions about the future of work and its potential for displacing workers.

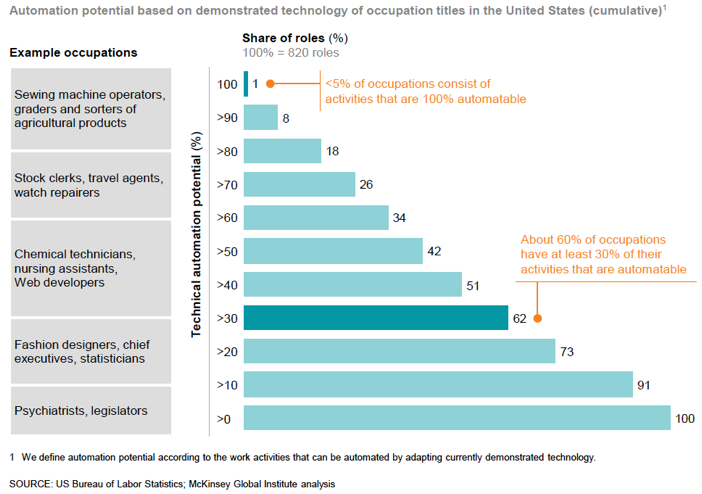

Estimates of the scale of threatened jobs over the next decade or two range from 9% to 47%, according to a 2016 White House research report. This is defined as those working in jobs where more than 70% of their activities can be automated. On average, nearly one-half (46%) of work activities in the country are currently automatable.

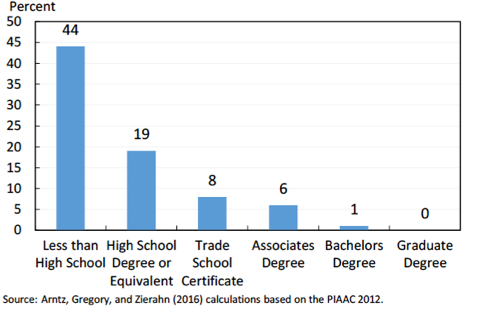

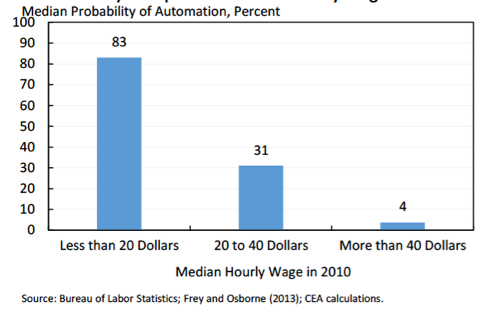

Most of this risk is concentrated among lower-paid, lower-skilled and less-educated workers. Workers earning below $20 per hour face a greater than 80% chance of displacement. More than two out of five workers without a high-school degree have job skills that are considered highly automatable. These projections should raise concerns about the ability of communities to tackle existing issues of social equity and affordable housing that could be exacerbated by automation.

Job tasks that are most susceptible include predictable physical tasks (which make up 8% of all work tasks), data processing (16%) processing and data collection (17%). On the other end of the spectrum, work that either involves managing others (7%) or applying expertise (14%) proves the least susceptible. However, even these jobs aren’t immune to some degree of automation.

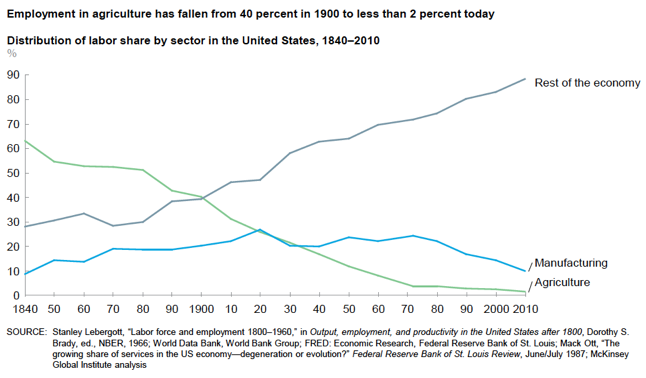

This magnitude of shifts in work activities over multiple decades is not unprecedented. The share of U.S. farm employment fell from 40% in 1900 to 2% in 2000, while the share of manufacturing employment fell from approximately 25% in 1950 to less than 10% in 2010. In both cases, new activities and jobs were created that offset those that disappeared.

What may be unprecedented is the pace of the change and scale of people affected. That said, a decline in immigration to the United States and the aging population/decline in the share of the working-age population will open economic-growth gaps at the same time that we’re seeing job disruption due to automation.

We will see large-scale shifts in workplace activities over the next century, and these trends are already underway. These shifts are inherent in automation technologies and also a consequence of a shifting labor demographic: Millennials, who already constitute the largest workforce population in the U.S., are demanding greater flexibility and autonomy than previous generations.

Preparing Our Workforce

Building an educated workforce and rethinking our educational and training programs is the most critical task in preparing for the future of an automated world, says Erik Brynjolfsson, director of the MIT Initiative on the Digital Economy and co-author of “The Second Machine Age: Work, Progress and; Prosperity in a Time of Brilliant Technologies.” Individuals will be required to have not only coding skills, he says, but also more diverse math, reading, interpersonal and creative skill sets.

According to the National League of Cities’ “The Future of Work in Cities” report, nearly all (95%) of the 11.6 million jobs that have been created since the last recession required some postsecondary education.

While science, technology, engineering and math (STEM) skills are emphasized, many employers are also looking for primary and secondary educational systems to address gaps in “workplace competencies” like teamwork, problem-solving and communication. STEM skills may power new technologies, but the “soft skills” of collaboration, critical thinking and interpersonal skills are vital components of the jobs likely to endure automation. The balance of these skills will remain essential to prepare students with the human-digital capabilities they will need.

As more restaurant orders are automated and shopping moves further online, humans who work in these retail sectors will be expected to provide the customer with something “extra,” something social, to shift toward selling more personalized or unique experiences – what the experts call the “commodification of experience.”

New technology and peer-to-peer platforms as well as a greater emphasis on personal craftsmanship and human ability have fueled the growth of a creative class of individuals capable of marketing their work from home. This emphasis will likely continue to spread across the lower-skilled labor market, where individuality and a personal touch are valued and where services cannot be outsourced or easily automated.

Cities should encourage entrepreneurship and reduce barriers to innovation. For example, they can limit the number of occupational licenses necessary or streamline the process to get new licenses.

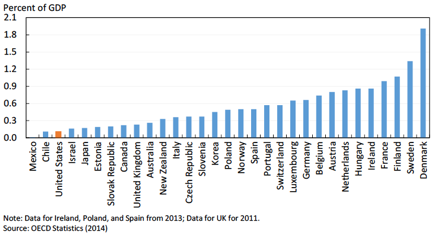

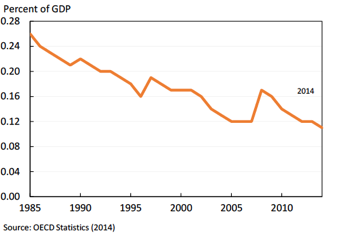

The 21st-century worker will need a lifelong learning mindset to be successful and use digital resources to enable digital skills development. The nation will need to reverse its declining investment in our workforce if we are going to sufficiently prepare people for future jobs in an era of automated work.

Public Expenditure on Active Labor Market Programs

Case Studies Blaze the Trail

Scholarship Sacramento: Valley Vision, based in Sacramento, created a comprehensive online platform of local scholarships for students who live in the Sacramento region to help address the growing costs of advanced education-tuition at four-year public colleges is up 33% since the 2007-08 school year. They have identified approximately $350,000 in local scholarship funds in Sacramento County. Since the program’s inception in 2013, it has reached more than 1,000 students and their families with scholarship education and one-on-one and group mentoring.

Degrees At Work in Louisville: In 2010, Louisville made a citywide commitment to add 55,000 college degrees (40,000 bachelor’s and 15,000 associate degrees) to its workforce by 2020. They first targeted the lowest-hanging fruit – the more than 90,000 local adults who had already completed some college coursework. Degrees At Work aims to help 15,000 working adults earn degrees by 2020, working with local companies that have stepped up to provide tuition reimbursement, college advising and flexible schedules for their employees.

Long Beach Internship Challenge: Mayor Robert Garcia has championed a partnership between the school district and the business community to connect students and school curricula to real-life workplace experiences in healthcare, information technology, business, entertainment and other industries with the goal of doubling the number of internships to better prepare Long Beach’s workforce.

A like-minded workforce development initiative in Monterey, Monterey Bay Internships, consolidates information about internship opportunities throughout the region to connect employers and educated, enthusiastic candidates. Launched last year, the free service reached nearly 1,200 users by December 2016.

Tucson Commercialized Advisory Network: The City of Tucson and the University of Arizona have formed the Commercialized Advisory Network to link 750 industry professionals and provide guidance and opportunities to tech entrepreneurs in the city. The result: 200 new patents, 86 licenses and 12 new startups in biotech, materials science, software and publishing.

A Regional Innovation Hub in Arkansas: The emergence of innovation hubs – where maker spaces and technology start-ups have become a part of the business landscape – can also be access points where cities can connect education and business. In North Little Rock, the Arkansas Regional Innovation Hub has opened its door to young people, offering free after-school classes, clubs, workshops and summer programs to help young people experience art, technology and entrepreneurship.

Communities will also need infrastructure like broadband Internet and other basic services (see the April LPU article on “Broadband for Better Communities“) that can help people use technology to take advantage of a range of opportunities to stay competitive in the evolving marketplace – from online learning and telecommuting to creating and selling their own products.

Leaders: The Future Is Now

Policymakers, business leaders and workers themselves must not wait to take action. Already, there are measures that can be taken today to prepare, and help communities begin to capture the economic and social opportunities offered by automation, even as they see to avoid the drawbacks.

Local Government Commission Newsletters

Livable Places Update

CURRENTS Newsletter

CivicSpark™ Newsletter

LGC Newsletters

Keep up to date with LGC’s newsletters!

Livable Places Update – April

April’s article: Microtransit: Right-Sizing Transportation to Improve Community Mobility

Currents: Spring 2019

Currents provides readers with current information on energy issues affecting local governments in California.

CivicSpark Newsletter – March

This monthly CivicSpark newsletter features updates on CivicSpark projects and highlights.