Revisiting Single-Family Zoning: Creating Options for a More Affordable Housing Supply

California’s housing shortage has reached a crisis of historic proportions.

Governor Newsom has called for the production of 3.5 million new housing units by 2025. According to state housing officials 180,000 new units are needed annually just to keep pace with existing growth, far above the 80,000 new homes produced on average over the last 10 years.

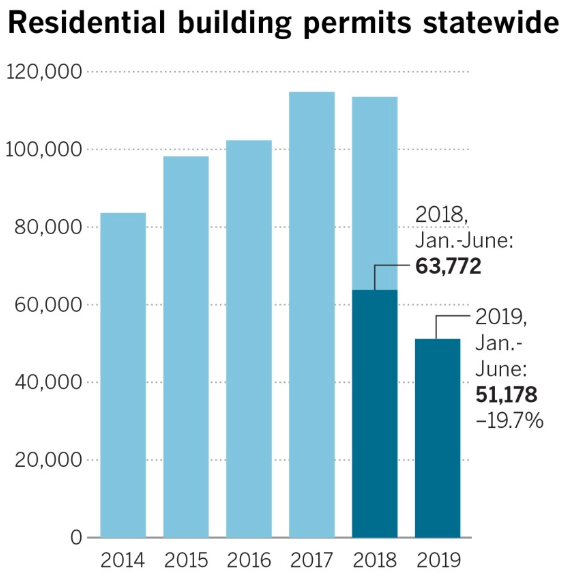

To make matters worse, we’re heading in the wrong direction. In the first six months of 2019, new residential building permits in California have decreased by nearly 20% from the same time period in 2018. Permits for multi-family apartment buildings have declined by an even greater rate across the state, falling 42.2%.

There are lots of reasons for the slowdown, some of which are beyond the control of local and state policymakers. One powerful lever that policymakers can control, however, is zoning regulations. This mechanism has received a lot of media attention with action like the recent legislative changes in Minneapolis and Oregon.

An Obstacle to Affordable Housing

Nearly two-thirds of the residences in California are currently single-family homes, according to U.S. census data. And between one-half and three-quarters of the developable land in the state is zoned for single-family housing only, according to a 2018 survey by UC Berkeley’s Terner Center for Housing Innovation.

The state can no longer dedicate that much land to single-family homes if California housing is to become more affordable and if political leaders want to meet aggressive goals to reduce greenhouse gas emissions, said Carol Galante, the Terner Center’s director.

“I do not think it’s possible to solve housing-affordability problems and meet climate-change goals without dealing with this issue of single-family homes only,” Galante said. “We have population growth. We have job growth. People need to live somewhere, and they’re now competing for a very limited supply.”

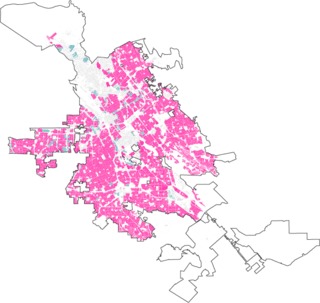

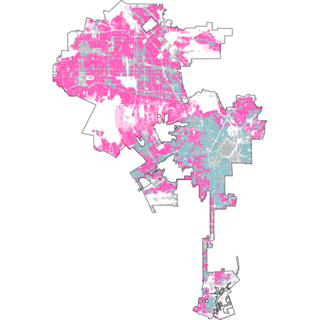

In San Jose, single-family zoning affects 94% of residential land, according to the New York Times. Even large metro areas like Los Angeles have approximately 62% of their residential land zoned for single-family housing. As a whole, residential areas in the state are about 80% single-family homes.

Across the state, communities big and small, wealthy and poor, north and south, coastal and inland have large sections zoned for single-family homes. The wealthy Bay Area town of Atherton sets aside at least 95% of its land for single-family housing, according to a UC Berkeley survey.

Between one-half and three-quarters of the developable land in Sacramento and Stockton is also reserved for single-family homes.

Figure 2. Single-Family Zoning shown in pink and Multi-Family Zoning in teal across the urban centers of San Jose (left) and Los Angeles (right)

Single-family zoning, made popular in the mid-1900’s as a staple of the American Dream, restricts every other type of housing, including senior housing, duplexes, apartment buildings, low-income housing and student housing. In turn, people are pushed farther and farther away creating transportation and pollution problems that affect everyone. This type of zoning generally separated working-class families from affluent ones, and has contributed to racial and economic segregation in cities.

Changing the Rules

In the early 20th century, court rulings blocked zoning rules that explicitly barred nonwhite people from living in certain neighborhoods. But in 1926, the U.S. Supreme Court decided that proposals banning apartment buildings and allowing only single-family homes in neighborhoods were constitutional, even though many supporters of those plans pushed the zoning as a means to segregate their communities, according to “Segregation by Design” by UC Merced associate professor Jessica Trounstine. The idea that you could legislate out not just gritty industrial facilities but also renters spread rapidly.

Overall, single-family homes are not disappearing or at risk of becoming a minority share of the U.S. housing stock any time soon. But some regions are now working to at least diversify their options. Far from Manhattan-style skyscrapers, many communities are looking at “the missing middle” between single-family homes and high-rise apartment buildings.

Building types such as duplexes, triplexes, fourplexes and small apartment buildings are not only more affordable and inclusive for renters, but they also allow more people to find ways to live in a walkable, livable neighborhood.

Coupled with smart transit planning and transit-oriented development, filling in the Missing Middle also has the potential to simultaneously ease the housing crisis, contribute to achieving the state’s climate goals, and create more vibrant local economies around urban centers.

Community and elected leaders throughout the U.S. are beginning to undo single-family zoning laws and create new alternatives.

Minneapolis: A long-range plan for equitable multi-family zoning

In 2018, Minneapolis became the first major U.S. city to end single-family zoning. With a 12-1 vote, the City Council passed Minneapolis 2040, a comprehensive plan to permit two- or three-family homes throughout the city’s residential neighborhoods, abolish parking minimums for all new construction, and allow high-density buildings along transit corridors.

Although there was strong consensus on the Council, the plan faced strong opposition from a vocal minority of residents, which included a lawsuit that didn’t hold up in court.

Other cities have attempted block-by-block or “spot” upzoning, but this is time-consuming and opens a contentious debate about which neighborhoods to upzone first. Block-by-block reform traditionally has allowed neighborhoods with more power and influence to slow or halt progress entirely, and hence tends to put multi-family zones more often in lower-income neighborhoods.

“Large swaths of our city are exclusively zoned for single-family homes, so unless you have the ability to build a very large home on a very large lot, you can’t live in the neighborhood,” said Minneapolis Mayor Jacob Frey.

Single-family home zoning was devised as a legal way to keep African Americans and other communities of color from moving into certain neighborhoods, and it still functions as an effective barrier today. Abolishing restrictive zoning, according to Frey, was part of a general consensus that Minneapolis ought to begin to mend the damage wrought in pursuit of segregation.

By opening up their wealthiest, most exclusive districts to triplexes, the City hopes to create new opportunities for people to move for schools or a job, provide a way for aging residents to downsize without leaving their neighborhoods, help ease the affordability crunch citywide, and stem the displacement of lower-income residents in gentrifying areas.

Homeownership in Minneapolis diverges along racial lines, with the rates of people of color lagging between 20 and 35 percentage points behind that of white property owners.

More rental supply citywide, in addition to new additional investment in affordable housing, is expected to help residents in a city where (like in most American cities) the majority of people live in rental housing.

Oregon: Opening single-family zones to multi-family statewide

Earlier this month, Oregon became the first state to eliminate single-family zoning in residential areas across the entire state.

House Bill 2001, signed into law by Governor Katie Brown, requires cities with more than 25,000 residents to allow duplexes, triplexes, fourplexes and “cottage clusters” on every lot on land zoned for single-family housing. Cities with at least 10,000 residents are required to allow duplexes in single-family zones.

The legislation was supported by a diverse coalition of interest groups, highlighting the potential of “missing middle housing” to advance equity, affordability and improved quality of life for all residents.

California: Pushing for state legislation and local action

In May California’s state senate shelved Senate Bill 50, legislation introduced by Senator Scott Wiener, which would have allowed mid-rise apartment construction near mass transit as well as small apartment complexes and town homes in wealthy communities in large counties (including Los Angeles). Wiener has continued efforts to build a growing coalition in support of SB 50.

Mayors in some of California’s biggest cities are considering doing away with zoning that allows only for single-family homes.

At a housing forum in the Bay Area over the summer, Oakland Mayor Libby Schaaf and Sacramento Mayor Darrell Steinberg said they supported ending single-family-only zoning in their communities, while San Jose Mayor Sam Liccardo said his city was also considering doing so. The trio has endorsed SB 50, as has San Francisco Mayor London Breed.

Changing course for our housing future

Our housing and land-use decisions have been on autopilot for decades. Zoning restrictions that once seemed appropriate are now throttling progress and contributing to a housing crisis of historic proportions. It’s time to create a new blueprint for the future – one that is sustainable, livable and inclusive.

Resources

- California’s Future: Housing – Public Policy Institute of California

- California’s Home Builders are Pulling Back – LA Times

- The Political Battle Over California’s Suburban Dream – CityLab

- What is Missing Middle Housing? – Opticos Design

- Why Minneapolis Just Made Zoning History – CityLab

- ‘Missing Middle’ Neighborhood Opens – Public Square, CNU

Local Government Commission Newsletters

Livable Places Update

CURRENTS Newsletter

CivicSpark™ Newsletter

LGC Newsletters

Keep up to date with LGC’s newsletters!

Livable Places Update – April

April’s article: Microtransit: Right-Sizing Transportation to Improve Community Mobility

Currents: Spring 2019

Currents provides readers with current information on energy issues affecting local governments in California.

CivicSpark Newsletter – March

This monthly CivicSpark newsletter features updates on CivicSpark projects and highlights.